anticopyright

2017

Anthony Weir

|

ABSINTHE

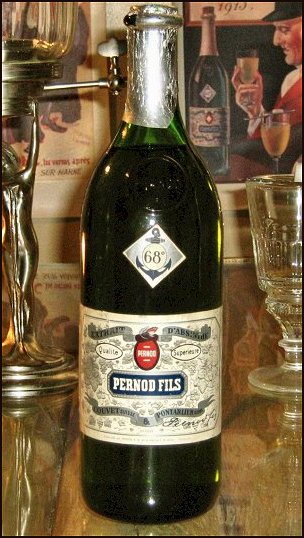

When I first drank pastis, the very smell made me nauseous. Pastis was created in the twentieth century; the term (an Occitanian word meaning ‘mixture', related to the 'pistou' or pesto of Provence, and also used to describe the original plum-pudding from Guyenne) first appeared, with reference to the drink, in 1932. It was a substitute for its much-demonised nineteenth-century progenitor: Absinthe. This was a strong, unsweetened spirit of Alpine origin based on the Wormwood family (mainly Artemisia absinthum), especially the original eighteenth-century recipe of Dr Pierre Ordinaire, later popularised with huge commercial success by Henri-Louis Pernod. Wormwood is a bitter, 'cleansing' herb, and thus is very good for the stomach and gut. As its name implies, it could shock a tapeworm into letting go. If you feel queasy or liverish, or have drunk too much, to chew a leaf or two of absinthe can work wonders. It was thus a staple plant in mediæval and monastic gardens.

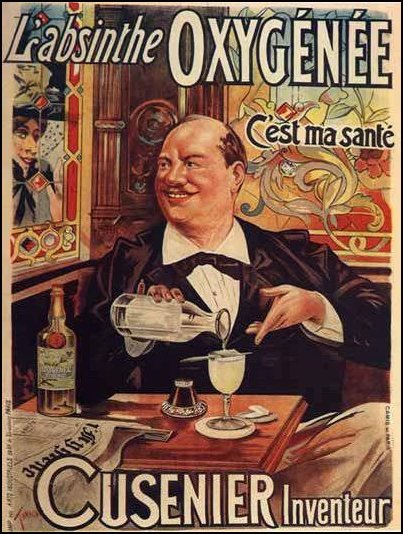

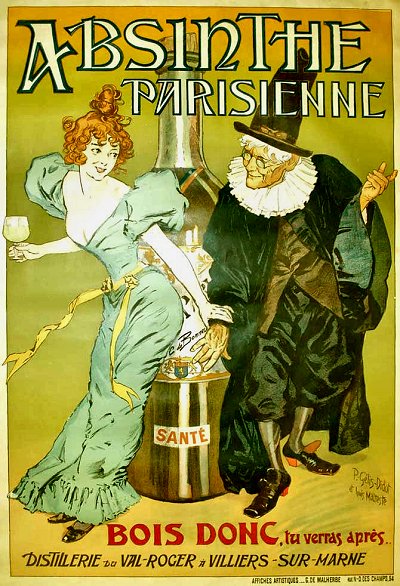

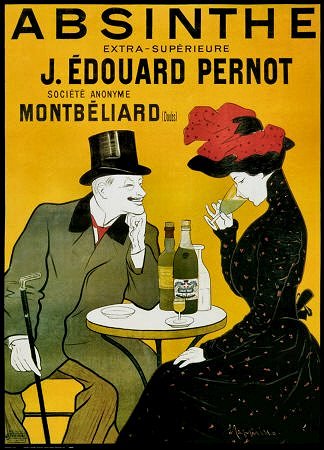

The absinthe leaf, together with other bitter herbs, was considered inedible, and was no longer used, except by travelling healers, who were victims of police oppression in France, because, like all itinerants, they were thought to transmit sedition against the corrupt rule of Napoleon III. But the tradition of its beneficent properties lingered, and it was added to alcohol partly in order to counteract some of alcohol's more deleterious side-effects. It was 'all the rage' in the 1880s and 1890s, and the French equivalent of the demure British Afternoon Tea was l'Heure d'Absinthe, around 5 pm. Because of its potency (real or imagined) consumption was limited to one glass, sipped genteelly. But naturally, the temptation to 'pub-crawl' was too great for those with miserable lives and little self-control or amour-propre. In the more proletarian establishments, from Le Rat Mort in the Place Pigalle to Le Caveau des Innocents close to Les Halles, poor-quality (probably toxic) absinthe could be drunk unmonitored, as was the less expensive rot-gut colonial red wine from Algeria.

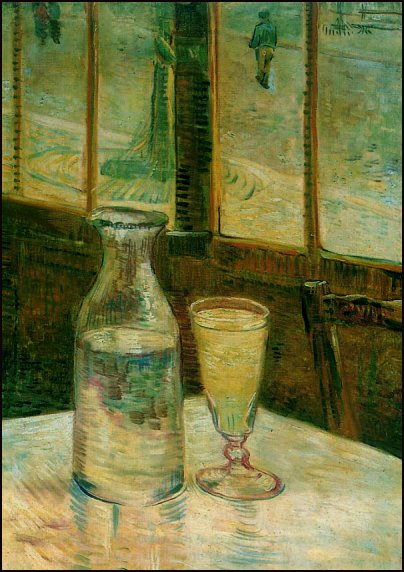

Already-sweetened, hence syrupy, alcohols (like crème-de-menthe) appeal only to the most infantile or degraded palates, so the very bitter absinthe was mixed with sugar and water after it left the bottle. Most absinthe recipes included Florence fennel and green aniseed as well as other plant extracts (such as hyssop) to add colour and depth to the taste. The final sweetening was provided by the drinker, who dripped iced water through a sugar cube placed on an absinthe spoon into the green liquor below. Absinthe spoons can still be found in antique shops in France, and sugar cubes remain popular.

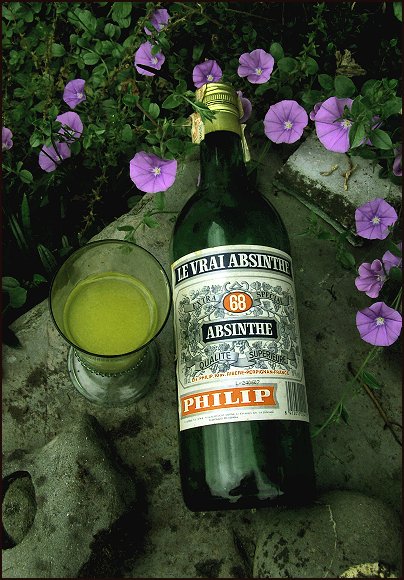

What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset ? The highest-quality absinthes were not wormwood-extract plus industrially-produced alcohol, but grape alcohol, or a basic marc to which were added actual distillates of the two kinds of wormwood, with hyssop, fennel etc. To this high-alcohol liquor a maceration of more native European plants (such as Veronica officinalis) in grape spirits was added, in order to hold its natural green colour. Such a high-quality product was complex and intense, and louched beautifully i.e. turned a lovely shade of pale green when water was added. Van Gogh of course never drank the good stuff, but a cheap and probably nasty product which turned out more yellow (like pastis) than green.

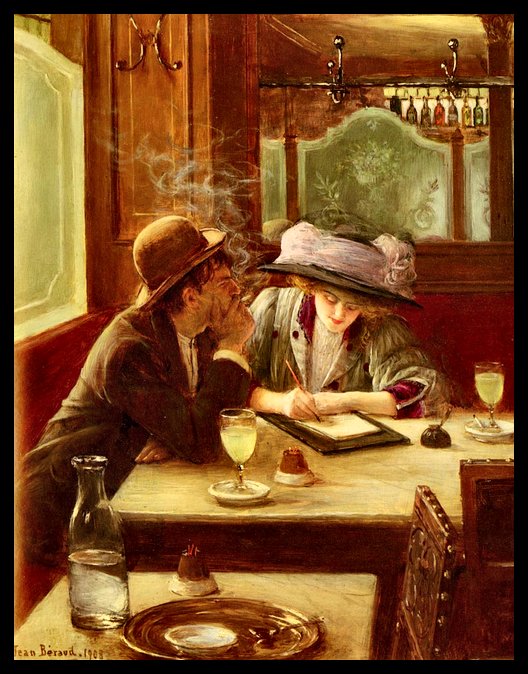

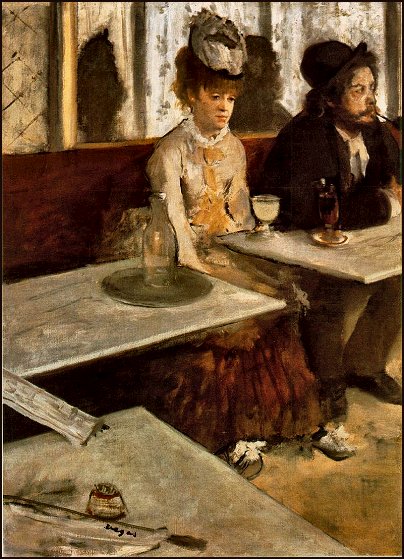

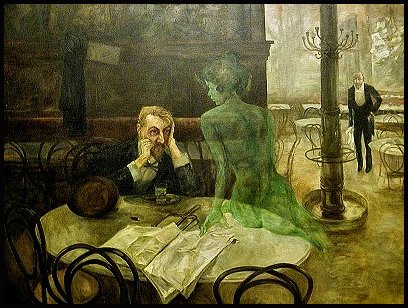

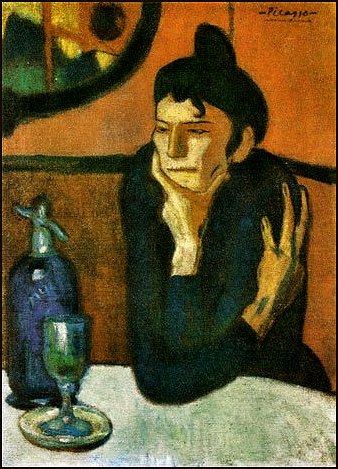

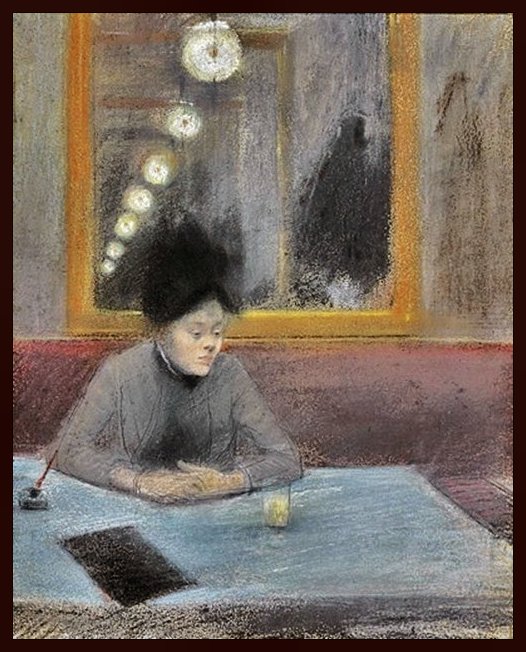

Here, the Green Fairy sits on the table of

a Paris brasserie,

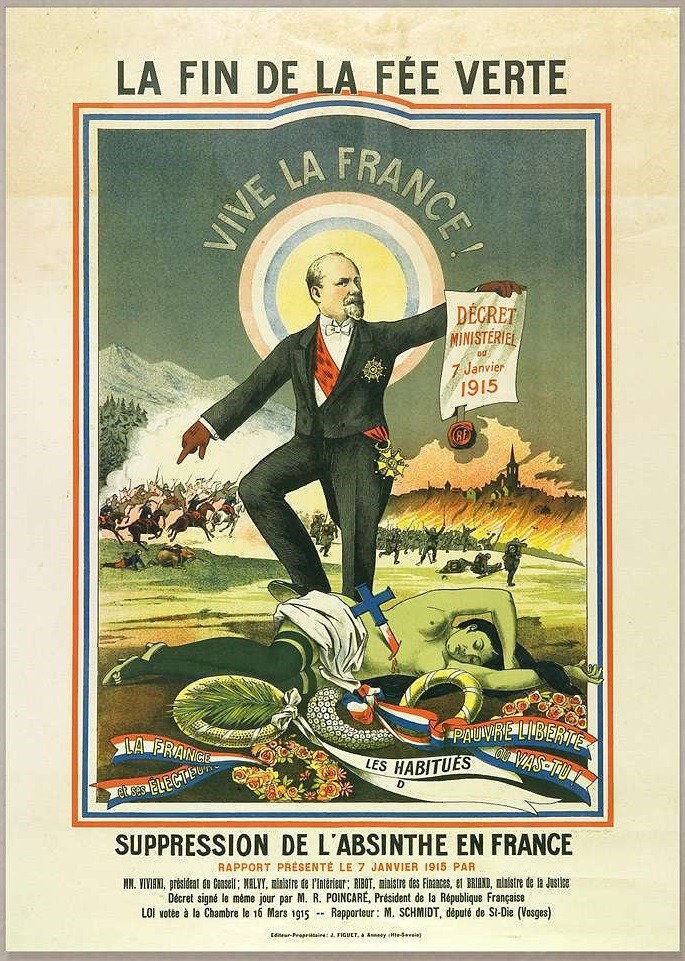

"The End of the Green Fairy" - with President Poincaré trampling her body as if she were Marianne, symbol of the Republic.

The European ban was lifted in 1998, and absinthe is now popular again - in cocktail bars. It is unlikely to dent the popularity of semi-sweet pastis, which remains by some margin the most widely consumed spirit in France - where it outsells whisky, gin and vodka combined. This product played on a coincidence (?) of name.

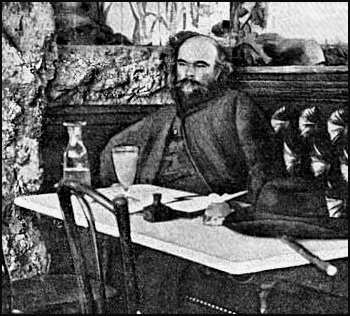

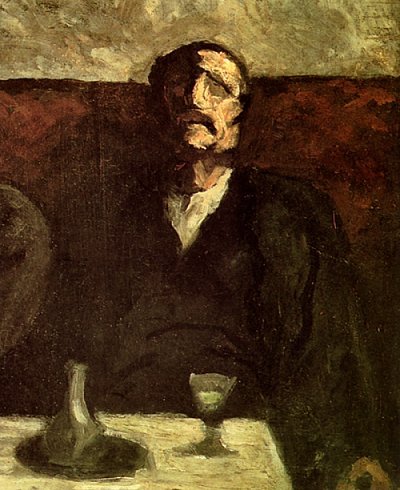

By this strict, two-ingredient definition, Pernod isn't a pastis at all but a boisson anisée, since it contains no liquorice; instead, its aniseed flavour is complemented by plants such as mint, coriander, angelica, tarragon (a relative of wormwood) and chamomile, and it is more highly sweetened than Ricard. Pastis 51 was originally a Pernod variant which did contain liquorice in contrast to the original, which bore the number 45. Other smaller brands include Sol-Anis, Casanis and Duval (both the latter produced in the same factory in Marseille) and the colourless Berger Blanc (now owned by the Franco-Polish group Belvédère). There are also 'artisanal' alternatives such as Eyguebelle, Jean Boyer and Henri Bardouin. The last of these is the most widely distributed of the three, and claims ‘grand cru' status - though the notion of the cru or ‘growth' is hard to sustain for a spirit whose main single ingredient is alcohol now derived from sugar-beet. The difference between Bardouin and its supermarket alternatives is in the complex recipe, containing (according to the company) some 65 different varieties of herbs and spice!. As a result, its taste somehow manages to be both complex and bland, and cloys the palate. In the south of France, Pernod is regarded as unforgiveably foreign and Parisian; Marseille, Provence and Languedoc (expecially Perpignan) are the 'home' of pastis. But to make your own, modern (lower-alcohol) Absinthe Surrogate is very easy. Simply buy a bottle of Casanis, Lidanis (from Lidl) or Duval (which cost little more than 12 euros a litre) and stuff a good sprig or four of Artemisia absinthum leaves or flowers into it, and leave for a week or so before you start drinking the wonderfully bitter ratafia which will result, and which you can strain and then mix like pastis with ice and water up to 5 times its volume - or just twice its volume if you like the taste of wormwood, as I do. Or drink it sec (neat) as a digestif. Some sprigs of hyssop will add more character. It will not be noticeably green. I leave it to your imagination and ingenuity to find an herbal ingredient which will make a pleasing pale green colour. It is worth noting that other, more common, plants contain thujone, notably Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) and Feverfew. These can be added to the mix, though the taste of feverfew is not as clean as that of absinthe. Common sage also contains some thujone. European Union harmonised laws now ban not absinthe but any drink that contains more than ten parts of thujone per million of liquid. This is a tiny amount - a fraction of what absinthe contained in its sordidly-glorious heyday. On no account buy the expensive confections now sold in fancy bottles with devil-strewn labels (some of them made in the real Bohemia) as 'real' absinthe. At best, these are complex flavourings - excellent for ice cream. At worst, they are sickly parodies, crude and cloying to the palate. The best are 70% alcohol and supplied with droppers - and excellent for macerating cannabis-buds (for several months) to produce a drink interesting mainly for those who like to play with herbs and concoctions. A high-class brand called L'Extrême d'Absente (made at Forcalquier in Provence) declares on its label that it contains 'up to' 35 milligrams of thujone per litre. The very first painting of absinthe may well be Daumier's Smokers - though only one of the two men sitting at a table is actually smoking, The other one has a glass and a carafe in front of him, and seems to be somewhat remote from his surroundiungs.

|